Corduroy is a multidimensional figure, set in tangibles and abstractions alike.

It’s the hero seeking danger in an action thriller novel; riding horseback; mud on Hampstead Heath one foggy morning — me, and a million teddy bear-colored hypoallergenic dogs splashing in the puddles. It’s what I want to wear to feel cozy and sturdy when my favorite pair of jeans have been worn in too much that week, adding richer textures to my outfits. It’s Woodstock, braided hair, septagenarians with stories to relay. It’s a line of oat flat white orders queuing on the street, or by the canal, or the hidden alleyway of a cafe you can’t find on Google Maps. It’s a sneaky grin, a soft kiss, an evening reading by the fire.

Over 100 of you liked this chocolate corduroy trench coat from my eBay digging two weeks ago. I’d like to think my sentiment is shared; there’s a sense of longing for textures to sink into yet feel entirely upright and postured in them.

In my rudimentary research, the fabric’s history points these feelings toward the nature of corduroy’s ebbs and flows in cultural status.

Fabric historians believe that corduroy originated from an Egyptian fabric called fustian. Like corduroy, fustian fabric has raised ridges, but is rougher and not as tightly woven. In 200 A.D., weavers in (then, the capital city) Al Fustat developed a blend of thick twills and coarse sateen fabrics to make them hearty enough to withstand brushing. Fustian was a highly sought after textile by the elite, particularly as trade routes opened by way of Italy and Spain, making the prosperous city a target of the early Crusades, and later eclipsed by neighboring Cairo.

Somehow, despite its origins reduced to rubble, fustian survived to pave a new path in Britain. There, textile manufacturers during the Industrial Revolution developed modern corduroy. Usually made with cotton, corduroy consists of three separate yarns woven together. The two primary yarns create a plain or a twill weave, and the third yarn intersperses into this weave in the filling direction, forming ridges that pass over at least four warp yarns. Its adaptability and structural integrity won the hearts of fashion elites.

The corduroy boom was short-lived: by the 19th century velvet had replaced corduroy in high society, and corduroy received the derogatory nickname “poor man’s velvet.” Qualities that once deemed the fabric flamboyant and pompous transitioned into utilitarian and working class. Romantic thoughts of corduroy quietened.

In the sixties and seventies, it was worn as a symbol of anti-establishment. Musicians, artists and directors, quirky people and peaceful people and politically active people, all gathered at the altar of corduroy. Corduroy could speak to pleasure and purpose alike. What would the Summer of Love be without it?

In 1973, the Chicago Tribune’s Marylin Stitz covered its return to the limelight, saying

“When you think about transitional dresses, playtime outfits, and back to school togs, one fabric comes to mind. Corduroy.

Why? Because it’s luxurious and functional at the same time. It can look dressed up or dressed down. It holds its shape and is easy to care for. It adapts well to clothing for your entire family. It’s durable—and economical.”

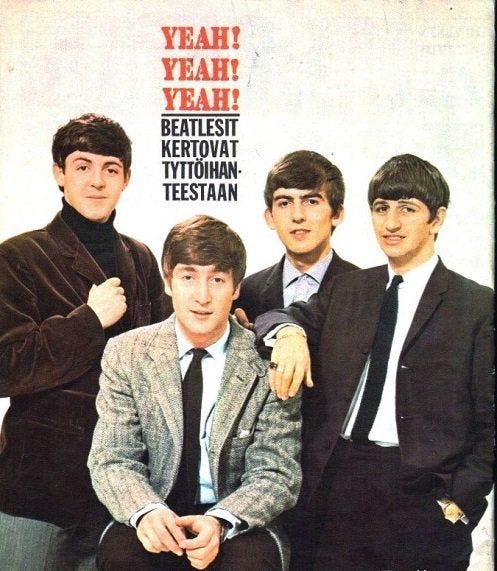

These tensions between high and low in the fabric’s history reflected the very real ones that existed in the mid-late 20th century. And no one established their sartorial connection to corduroy quite like Paul McCartney, George Harrison, John Lennon and Ringo Starr.

Author of Fashioning the Beatles: The Looks That Shook the World, Deirdre Kelly, noted their impact on the material: “There were other surprises, besides — George jump-starting the acid-wash denim trend, for example, and discovering corduroy, which the Beatles popularized, was initially an unfashionable cloth, reserved for the working class.” So Manchester cloth, corduroy’s well-known alias, found its way back via the world’s biggest band. Coincidence? I’d think not.

They really were decked out in it: newsboy caps from their film Help!, jackets with custom matching shoes (some cobblers refused this request, in fact). Kelly noted the Beatles often signalled “their essential nonconformist and subversive nature” in their fashion, communicating their disposition in each phase of the band. Corduroy was no different, and arguably of equal significance to their more androgynous or eccentric choices. Perhaps donning corduroy reminded the Beatles of home, too.

I first knew of love through the Beatles: it was the only music my grandparents would play outside of classical music. Carpooling to preschool and weekends with the family were spent passing CDs back and forth between my cousins and siblings in the back of the van, calling out our favorite songs to be added to the queue. I’d daydream out the window to Love Me Do, drum along to the transcendant trumpet solo in Penny Lane, and wonder how big love must grow to quantify it into Eight Days a Week.

Two summers ago, after a barbeque and group sunset swim, one of my mates softly strummed a few chords of Blackbird as we were all winding down in the basement of his flat in Brighton. Stunned and in a drunken haze, uncontrollable tears slipped down my cheeks. I caught them in palms at my chin. Somewhere across the English Channel, the Atlantic, and every sea, there I was in the back of my grandparent’s van. Where love started.

Corduroy’s position in culture wavers in favor. Similarly, production quality and environmental standards can be inconsistent. Its versatility, its forms of communication, its political transformations, though, lead me to deem it an object of affection.

Corduroy to fall in love with:

Vintage 80s Camel Corduroy Coat

Y2K Dolce Chocolate Corduroy Pants

<3

Man, if those RL black flares were my size... ;) Also, BIG hearts for this fabric, the Beatles, and my 'rents.

What a great read! The chocolate brown corduroy is simply chef’s kiss…